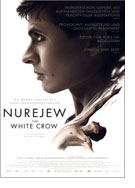

Opening 26 Sep 2019

Directed by:

Ralph Fiennes

Writing credits:

David Hare, Julie Kavanagh

Principal actors:

Oleg Ivenko, Ralph Fiennes, Louis Hofmann, Chulpan Khamatova, Sergei Polunin

Some of Russia’s best exports during the Cold War were its ballet dancers. Director Ralph Fiennes’ capsule biopic is about Rudolf Chametowitsch Nurejew, who was the first dancer to defect from the Soviet Union in 1961. Based on Julie Kavanagh’s book, Rudolf Nureyev: The Life, David Hare’s screenplay focuses on three pivotal points in Nureyev’s life: childhood, formative years, and early adulthood.

With an absent father, overburdened mother (Ravshana Kurkova) and three sisters, the young standoffish loner Rudi (Maksimilian Grigoriyev) is nicknamed “white crow.” At 17, Rudolf (Ivenko) begins training at Leningrad State Choreographic Institute in 1955; arrogantly demanding a better teacher, ballet master Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin (Fiennes’ portrayal is masterly) and Xenia (Khamatova) take special interest in him. Joining the Kirov Ballet under director Konstantin Sergeyev (Nebojsa Dugalic) in 1958, Nureyev’s rebellious, nonconformist attitude almost costs him dearly –touring with the troupe in then Western Europe. In Paris, and under KGB scrutiny, Nureyev ignores rules and mixes with the natives, including Pierre Lacotte (Raphaël Personnaz) and Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos) whose friendships subsequently make the difference.

In his debut role, professional Ukrainian dancer Oleg Ivenko superbly portrays Nureyev: his innate passion, ballet skills, sensual beauty, madness and character flaws. The film’s alluring aspects are its worthy cast, and production values – Mike Eley, cinematography, Ilan Eshkeri, music. Editor Barney Pilling employs color sequences and flashbacks: the childhood phase is starkly black and white with tonal values; Nureyev’s training phase is awash in muted ochre, and present day Paris with pastel mixed colors. Differentiating between the two later periods is difficult, particularly with the many characters involved. Furthermore, the latter phases’ use of massive architecture, doorways, and arches serving as thinly veiled analogies to the Communist mindset are not fleshed out, i.e. unnecessary. Notable sound design/camera angles attributing to pivotal phases conversely sometimes seem accidental.

The White Crow should pulsate simultaneously with Nureyev’s sensuality and flamboyant appétit de vivre; equally, considering the dancer broke many ballet norms, temperament is missing. Rather, guided by Fiennes’ reticence, with superfluous dramatizations, the lengthy film’s nebulousness can be annoying. To the contrary, as an introduction to one of the 20th century’s greatest ballet dancers, and synergy among artists, the film is marvelous. (Marinell Haegelin)