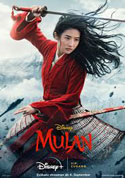

Opening 3 Sep 2020

Directed by:

Niki Caro

Writing credits:

Rick Jaffa, Amanda Silver, Elizabeth Martin, Lauren Hynek

Principal actors:

Yifei Liu, Donnie Yen, Li Gong, Jet Li, Jason Scott Lee

Chinese custom prescribes that a daughter bring honor (to her family) through marriage, but director Niki Caro brings honor by respecting the storyline in Disney’s live-action remake of its 1998 classic animated film. The Ballad of Mulan is Chinese folklore about a legendary female warrior that enlists in the army instead of her aged father. The tale commenced during the Northern and Southern dynasties (386 to 589 A.D.)—its first recorded extant text was from the 11th- or 12th-century. As the tale advanced over thousands of years, slight changes occurred to the fictional Mulan character, whose story in an inspiration to countless generations of young Chinese people. There are scores of iterations, although the 16th-century Xu Wei’s play gained popularity for the majority of latter-day adaptations.

To link the variances among the different Chinese interpretations, and considering its divergent audiences—Asian, the Disney traditional and traditional Chinese viewers—the filmmakers blended these influences for a more rounded, thoughtful and authentic film.

During Mulan’s fantastic opening sequence, Hua Zhou (Tzi Ma) laments not curtailing oldest daughter Mulan as an unruly child (Crystal Rao): “They call her a witch …talk to her,” hisses Hua Li (Rosalind Chao) to her husband as Zhou dithers. Younger sister Xiu (Xana Tang) adores Mulan. Now a free-spirited woman (Liu Yifei) and at matchmaking age, Zhou’s advice is sagacious; nevertheless, Mulan is saved by an imminent Rouran-Hun invasion. At the Chancellor’s (Nelson Lee) urging, the benevolent Emperor of China (Jet Li)—and onetime warrior—issues an edict conscripting a son from each family into the Imperial Chinese Army. Disguised as a man, Mulan ingeniously mixes with soldiers in Commander Tung’s (Donnie Yen) unit; she forms a special allegiance with the formidable Chen Honghui (Yoson An) during training. Concurrently, Bori Khan (Jason Scott Lee) leads his warriors on evermore-victorious attacks against Chinese garrisons, while strategizing with the shapeshifting witch Xian Lang (Li Gong). With the battle raging, positions are taken and choices are instantaneous, but ultimately it all comes down to the Emperor’s infinite wisdom, and a father’s love.

Led by Liu Yifei’s interpretive portrayal of Mulan, the cast is formidable. Providing great comic fun is the Matchmaker / Pei-Pei Cheng scene, and scenes with fellow solider trainees / Jun Yu, Jimmy Wong, and Doua Moua, and villains Scott Lee and Li Gong. Production values excel: Mandy Walker Cinematography, David Coulson Editing, Grant Major Production Design, Harry Gregson-Williams’ Music score—director Caro decided that instrumental versions of the original animation’s songs would be most effective. The richly detailed, vibrant culturally appropriate period garments heighten the heroine’s persona. Mulan harkens to Disney’s trove of beloved family favorites, but its rejuvenation includes an atypical, enduring “Princess” that is exhilarating and moving as only Disney can. (Marinell Haegelin)

This is not your 90’s Mulan. As a young girl, Mulan (Yufei Liu) always had too much Qi (the Chinese concept of a life force or energy flow through the body) for a girl. She was too impulsive and full of vitality, something which eventually, due to a series of mishaps, she was forced by her parents to tone down. As an adult, she still struggles to fit in with traditional feminine roles, bringing dishonor to her family as a result. When her aging father (Tzi Ma) is called up to serve the Imperial forces in their fight against northern invaders, Mulan takes it upon herself to save her father’s life and become a warrior who will bring honor to the family. The only problem is, women are most definitely not allowed to become warriors, and if she is discovered, she will be killed. Will she be able to harness her inner-strength to save the nation and bring honor to her family?

While it is important to give some credit to Mulan for daring to stray away from the source material of the eponymous 1998 Disney classic, this alone does not make the film either original or well-composed. In attempting to appeal to the Chinese market, several key factors from the original film had to be removed such as the dragon sidekick Mushu and the musical numbers. What was added in their place was a strong overreliance on the Chinese concept of Qi and the depiction of martial artists as superheroes whose bodies somehow defy the laws of physics. While there is nothing inherently wrong with these changes, the addition of Qi raises the question of whether Mulan is strong and capable due to her own personal determination and hard work or rather as a result of some mystical force she was lucky enough to be born with. While this might be clear to some audiences, others may see it as undermining the very feminist aspects that made the Disney animated film so refreshing. Mulan may have always struggled with some social conventions, but at the end of the day she is supposed to be a normal woman whose grit and desire to help her family drives her to become an outstanding soldier. In the 2020 version, it seems she was born for great things and needs only to find focus for her internal magic to accomplish her goals, something which feels like a bit of a cop-out for normal women who see equality not as something available only to special people, but to everyone.

In addition to the Qi problem, there is also Xianniang (Li Gong), the new witch character who features so prominently in the trailers. Far from being an important antagonist, she only exists to serve as a juxtaposition to Mulan’s honor obsession. You see, Xianniang has a sad backstory of being treated poorly by China’s sexist society which lead her down the dark path of witchcraft. She is the evil Mulan could easily become if she were not such an upstanding woman. The only problem is that Xianniang is actually too sympathetic and Mulan’s motivations seem foolish in comparison. Why stand up for an emperor and country who doesn’t respect your differences, would kill you for your honorable actions of trying to save your father, and generally gives women only a very narrow roll to play in life? The audience is never given a fulfilling answer to these questions, only the knowledge that of course the heroine Mulan will prove an exception to these strict rules because she is the special one. Yet the inclusion of Xianniang seems to undermine a rather simplistic heroic tale and make Mulan’s choices no longer seem so noble.

While the visual spectacle of the action sequences and cinematography may have made an adequate enough impact on audiences in the cinema to make up for the characterization failures, the fact that Mulan is now receiving primarily a digital release will do it no favors. For audiences seeking nostalgia, there is little left of the determined and spunky Mulan of the animated version and those who want something different will likely find the weak character development and cookie-cutter plot to be a disappointment. Maybe it is time for Disney to roll back on their efforts to cash in on nostalgia with live-action remakes of their classics and begin to focus once again on the thing they do best: making new quality animated films for the younger generation. (Rose Finlay)