Opening 3 Feb 2022

Directed by:

Maryam Moghadam, Behtash Sanaeeha

Writing credits:

Mehrdad Kouroshniya, Maryam Moghadam, Behtash Sanaeeha

Principal actors:

Maryam Moghadam, Alireza Sani Far, Pouria Rahimi Sam, Avin Poor Raoufi, Farid Ghobadi

In Tehran, women’s rights are minimal, i.e., a woman is regarded as her husband’s property. So, struggling for almost a year alone with 7-year-old, and deaf, Bita (Avin Poor Raoufi) establishes Mina’s (Maryam Moghadam) tenacity, albeit her mind-numbing job at the milk company, and having to coax Bita to attend school is enervating. Imagine then, when authorities inform the widow her Babak was falsely executed. More astonishingly, Mina, now a single woman, will receive full compensation for his wrongful death; she is bitter, resentful. She wants to clear Babak’s name with a public apology and takes steps accordingly.

Before long Babak's brother (Pouria Rahimi Sam) is friendlier; then he and father begin scheming what they think is best for Bita and Mina. Meanwhile, Reza (Alireza Sani), an unknown-to-her friend of Babak, unexpectedly presents himself to repay money owed. Subsequently, he serendipitously materializes when Mina needs help most. Unsurprisingly, a tentative friendship, bolstered by half-truths and secrets, evolves until and when Mina secures a major gain against Babak’s relatives. Her short-lived euphoria is replaced by strong, perhaps subjective, malice.

Iranians Behtash Sanaeeha and Maryam Moghadam co-wrote the screenplay and direct; Moghaddam’s acting debut, as Mina is impressive, as is young Purraoufi as Bita endearing. The discordance between the Mina character’s motivational reasoning and actions should have been expounded on, considering its importance for international audiences’ comprehension. Ballad of a White Cow’s Iranian societal norms, e.g., procedural restrictions and Islamic sharia law, is alien to many cultures, whereas heartfelt emotionality is universally experienced. Moghaddam’s performance had to manifest the distinction between the complexities Mina copes with, and her conflicted feelings. The film’s quiet simplicity is affected through Amin Jafari’s mostly stationary, discerningly watchful cinematography, and editors Ata Mehrad and Behtash Sanaeeha.

Then there is the white cow (in a prison yard where men line one wall and women the wall opposite). The longest chapter in the Koran is about The Cow, metaphorically referring to sacrifice and issues involving relationships, and culturally, economically, legally, et al. In the film, sacrifices abound on different levels with different characters and their choices, e.g., Reza at Mina’s dinner table. Nonetheless and to avoid spoilers, even though the misogynous culture is repugnant, some audience members will be reminded of the proverbial adage, ‘two wrongs don't make a right.’ (Marinell Haegelin)

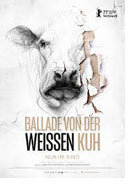

The Berlinale Film Festival has a long tradition of selecting strong Iranian films usually not from the current regime with its official stamp. Films such as the Oscar winner A Separation (2011) as well as About Elly (2009) both directed by Asghar Farhadi, and Taxi (2015) by Jafar Panahi, plus Closed Curtain (2013) by Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi. This film is no different—and is the third film collaboration over the years of Mayram Moqadam and Behtash Sanaeeha. The title alone is intriguing; as a westerner, the only comparison I could think have was, “Don’t cry over spilled milk.” However, with further investigation I came upon the Muslim symbolism of the sacred white cow—pure and honored. The white cow reminds us to tread lightly, to reach our goals without harming others. The question remains: is this possible in present day Iran? The Ballad of the White Cow shows us a modern Iran, yet reveals a repressive society that is indifferent to those individuals struggling to survive. Religious values control every aspect of life, cementing the possibilities of ruining lives among their unsuspecting victims.

Mina (Mayam Moqadam) struggles financially to support herself and her hearing-impaired daughter after the arrest and execution of her husband, Babek. She seeks financial help from the government to mitigate her situation, but is suddenly confronted with the shocking news that her husband was wrongfully executed. The bureaucrats apologize for this miscarriage of justice and are willing to pay financial compensation. But Mina is not satisfied: she demands an official apology, to erase this stain against the family name. Yes, definitely worth fighting for—but can she afford it? Just when all appears lost, a stranger, Reza (Alireza Sani Far) shows up, claiming to owe money to her deceased husband. Reza is willing to pay off the debt—but his actions arouse her suspicions—and once again putting her reputation at stake. To uphold her honor, she has no choice but to proceed with great caution. Successful at many film festivals, and definitely one worthy of seeing, it is an intelligent film that questions society’s choice of values as well as the pressures that comes from this society. (Shelly Schoeneshoefer)