Opening 22 Dec 2022

Directed by:

Giuseppe Tornatore

Writing credits:

Giuseppe Tornatore

A metronome paces the opening sequence of Ennio; his daily routine is crosscut with excerpts from family, friends, and colleagues: “He wrote music without playing it,” “individualist,” “ahead of times,” “in the first notes you know it’s him,” before entering his uniquely personal studio. Scores are strewn everywhere, piled high and yet, for this creative genius frightfully organized. Cozying to the topic sans braggadocio, the Maestro talks about his life beginning in 1928 Rome; Italy was his lifelong residence. Explaining he knew what enthused him his father Mario, a trumpeter, had “decided I’d be a trumpet player.” At 12 Ennio began studying at the Saint Cecilia Conservatory receiving a trumpet degree in 1946, and in band arrangement in 1954 with a 9.5/10 from the great Italian composer / educator Goffredo Petrassi.

In 1950 Ennio met future wife Maria Travia and transitioned from jobs playing trumpet to an RCA Victor studio arranger; writing radio program’s background music led to film work and he learned intriguing techniques. Retaining that toolbox, he started ghost-writing music for film and theater. In 1956 he and Maria married, and to support their growing family (four children) he arranged pop music (Paul Anka, Mina, Andrea Bocelli, etc.) for Italy’s RAI broadcasting service. Morricone’s debut film score was Luciano Salce's 1961 Il Federale (The Fascist); he went on to score over 500 films and more than 70 award-winners, plus all of the Italian directors’ Sergio Leone (childhood schoolmates) and Giuseppe Tornatore films. When Bruce Springsteen first saw The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) and heard the music he thought, “There’s something going on here.”

At home and comfortably seated, Ennio’s lively detailed descriptions about “three tone chords,” Bach or describing, while humming notes, countless songs / scores he composed is incredibly impressive. He laughs and jokes while recounting the breadth of his career, passion for playing chess and about creative innovations used for productions lacking funding, e.g., whips cracking, gun shots, Jew’s harps, trumpets, etc. in the Dollars Trilogy. Of Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso Ennio says, “Working on that film brought me a lot of joy.”

Morricone’s legendary divergent, creatively eclectic style opened unexplored vistas for composers, while also influencing artists across the broad sweep of music, and film genres from westerns to Dario Argento horror / cult to experimental movies. Guitarist Pat Metheny admiringly says, “He’s the only one who understands the guitar,” Hans Zimmer: “Morricone’s very good at creating a character with sound,” while Joan Baez says of their collaborative song “Here’s to You” for Giuliano Montaldo’s Sacco & Vanzetti (1971), “That song’s not just pop,” and Bernardo Bertolucci: “[he] also knows how to use silence.”

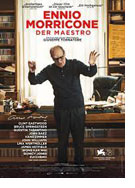

That comradery permeates director Giuseppe Tornatore’s masterpiece, Ennio Morricone – Die Maestro. Morricone’s prolific body of work, from jazz to neo-classical cantatas to television / advertisements, Bruce Springsteen succinctly summarizes “has probably been listened to and influenced more people especially in the last 20 years.” Scarcely covering the small man’s larger than life contributions to the 20th and 21st centuries the film’s great emotional depth and illuminating archival material has heart – Ennio Morricone’s legacy. (Marinell Haegelin)