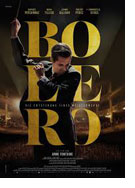

Opening 6 Mar 2025

Directed by:

Anne Fontaine

Writing credits:

Anne Fontaine, Claire Barré, Pierre Trividic, Jacques Fieschi, Frere Jean-Pierre Longeat

Principal actors:

Raphaël Personnaz, Doria Tillier, Jeanne Balibar, Emmanuelle Devos, Vincent Perez

“It (Boléro) can be heard somewhere in the world every fifteen minutes.” France’s renowned Maurice Ravel composed the large orchestral work for Ida Rubinstein, dancer, actress, Belle Époque figure and art patron, for a ballet in 1928. Under Ravel’s creativity sway and musicality daring, following stymied inspirations and attempts, the piece emerged with a life of its own in the form of a Spanish dance bolero in 3/4 time—rhythmic and melodious with harmonically pronounced, punctuated repetitiveness.

La mère maquerelle (Florence Ben Sadoun) fosters and encourages her son Maurice’s (Raphaël Personnaz) passion as he applies to the premier Paris Conservatoire music college. Constantly hearing music internally is what differentiates Ravel from contemporaries; Maurice broods over compositions for months before penning a note on staves. (Ravel’s lifetime body of work is relatively small.) Attending a soiree with friend Cipa (Vincent Perez), the Russian enfant terrible and dancer Ida Rubinstein (Jeanne Balibar) captures Ravel’s attention, with help from Russian friend Misia Sert (Doria Tillier). Ida commissions the ballet, instructing Ravel that she wants erotica, yet flowery, dreamy and, per his working reputation, i.e., minutely, painstakingly slow, Ida allows for more than enough time. It is years before Ravel finishes—this is his last completed piece before deteriorating health prohibits his composing/performing again. In 1928, Rubinstein’s ballet premiers to a full house at the Paris Opéra.

Belgium director Anne Fontaine and Claire Barré’s co-written screenplay is based somewhat on Marcel Marnat’s monograph, Maurice Ravel. Raphaël Personnaz’s brilliant performance—the quintessence movements of a pianist, conductor, composer—leads the stellar ensemble depicting bygone societal norms and groundbreaking advancements in the arts. Riton Dupire-Clément’s production design with Mélyssandre Manem’s set design lays the groundwork. Christophe Beaucarne’s fluidly glamorous, seductive camerawork demonstrates flexuosity through sometimes intricate mise en scene, e.g., Maurice and Misia playing the piano together. However, Thibaut Damade’s always fluid editing is mostly confusing. Story collaboration from Pierre Trividic, Jacques Fieschi, and Frere Jean-Pierre Longeat might have had a role in Bolero’s bewildering bits. The film’s two-hour length is too short for this early twentieth century composer, ranked among the most influential with standout musical craftmanship, biography, and yet too long to focus on Ravel’s best-known work, then cram his life story around it. That said, the music ensures audiences an auditive delight. (Marinell Haegelin)